En esta nota, citan un testimonio que me dio el vocero de los jesuitas en 2005.

Pope Francis: a man of joy and humility, or harsh and unbending?

Conflicting accounts of the former Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio's character have emerged ce his election

Pope Francis in Rome on his first day as pontiff. Photograph: Alessandro Bianchi/Reuters

The clerical career of Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the 266th Bishop of Rome, is bookended by two joyous dates. The first is 13 December 1969, the day on which the young Argentinian, on the brink of his 33rd birthday, was ordained a Jesuit priest. The second is 13 March 2013 when, at 7.06pm local time, white smoked curled into the Vatican night to confirm his surprise election as pope.

But there is a third, less celebrated, date in that career, a date that has already begun to haunt the first week of Francis's papacy from a distance of almost 40 years.

On the morning of Sunday 23 May 1976, more than 100 soldiers and marines climbed out of police cars and military lorries outside a church in the Bajo Flores slum neighbourhood of southern Buenos Aires and kidnapped two Jesuit priests, Orlando Yorio and Francisco Jalics. The pair were held and tortured at the infamous Naval School of Mechanics for five months.

After their release, the priests accused Bergoglio, the leader of the Jesuit order in Argentina, of abandoning them to the military junta. By withdrawing his protection after they refused to stop visiting the slums, and refusing to endorse their work, they said, Bergoglio all but delivered them up to the authorities.

Pope Francis has long denied the accusations. In 2005, when they resurfaced as he attended the conclave that elected Benedict XVI – and in which he reportedly finished second – he dismissed them as "old slander". Far from abandoning Yorio and Jalics – despite the fact that they had broken their Jesuit vow of obedience – he has insisted he did everything he could to save them, even interceding on their behalf with the Argentinian dictator José Rafael Videla and Eduardo Massera, head of the navy.

Pope Francis, then Jorge Bergoglio, back row centre in a family photograph. Photograph: AP

Pope Francis, then Jorge Bergoglio, back row centre in a family photograph. Photograph: AP

On Friday, Jalics broke his long silence to say that he had become "reconciled" to what happened after meeting Bergoglio in 2000. He made no further comment, nor did he withdraw the allegations he and his fellow kidnapped Jesuit had made.

The pope and the Vatican will be hoping that their denials and Jalics's late intervention will finally lay the matter to rest and allow Francis to begin his papacy in earnest. But even should the clamour from withinArgentina die down, Francis has other critics to face from the order for which he was ordained: the Society of Jesus.

Despite waiting very nearly five centuries to see one of their own on the papal throne, many Jesuits have been lukewarm at best about the pontiff, and, at worst, deeply suspicious.

Much of the distrust stems from Francis's six years as Jesuit provincial of Argentina – a period that included the kidnapping of Yorio and Jalics. His leadership was marked by an authoritarian and conservative outlook, which did not sit well with the traditionally independent-minded order. He was also fiercely opposed to liberation theology, which, with its radical elision of Christ's teachings and economics, attracted so many of the priests ministering to the poorest people of the Latin America in the 1970s and 80s.

As Michael Walsh, a papal historian and former Jesuit, puts it, some members of the order were "not altogether enthusiastic" about Cardinal Bergoglio. "As a provincial, he was extremely strict and fairly conservative, which goes against the grain of the society," said Walsh. "He did attend the general congregation that elected the predecessor of Adolfo Nicolás [the current head of the Jesuits] and people there felt that, without ever separating himself from it, he was at a distance from the society."

The official Jesuit reaction to Bergoglio's election as pope this week was scarcely effusive.

"All of us Jesuits accompany with our prayers our brother and we thank him for his generosity in accepting the responsibility of guiding the church at this crucial time," said Nicolás in a statement.

Other have been far more forthright.

The then Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio takes public transport in Argentina as archbishop of Buenos Aires in 2008. Photograph: Reuters

The then Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio takes public transport in Argentina as archbishop of Buenos Aires in 2008. Photograph: Reuters

Eight years ago, before the last conclave, the Jesuits' official spokesman, José María de Vera, characterised the cardinal as a priest who "doesn't identify himself as a 100% Jesuit". De Vera also told the Argentinian journalist Sebastián Lacunza: "He has said that there are some things in the order that he likes and others that he doesn't." The estrangement, he said, began to grow following the allegations made by the kidnapped priests. "He has had no relations with the order since the problems of the two priests – Yorio and Jalics – who went missing," said De Vera. Asked whether he believed the pair's allegations, he replied: "Of course. One of them is alive, and he lives in Germany, I believe."

It has not gone unnoticed that Bergoglio allowed it to be known that he chose his papal name to honour St Francis of Assisi rather than the Jesuit saint Francis Xavier. The distancing has gone hand in hand with the tightening of a new bond with the conservative Communion and Liberation movement (CL), which was founded by an Italian priest, the late Father Luigi Giussani.

Before the Conclave, the National Catholic Reporter published a profile of the then cardinal Bergoglio in which it noted he had spoken at CL's annual gathering in the Italian coastal resort of Rimini and presented Giussani's books at literary fairs in Argentina. This was certainly unusual behaviour for the member of an order whose relations with CL are, at best, cool.

Some, however, claim the gap between Francis and his order is narrowing and that the past disagreements can equally be explained by a simple clash of personalities. "Everyone has their own way," said Father José María Sang, a former student of Francis who now runs the Colegio Máximo de San Miguel, Argentina's main Jesuit training centre.

"There may have been differences in the past. But from what I have seen in recent years, there is a good relationship."

Postcards of the new Pope Francis on sale in Rome. Photograph: Dmitry Lovetsky/AP

Postcards of the new Pope Francis on sale in Rome. Photograph: Dmitry Lovetsky/AP

Sang, who recalls his former mentor as an earnest, well-prepared teacher with a strong spiritual orientation, also believes that those seeking to pigeonhole the new pope as conservative or progressive are missing the point.

"These terms are political, not religious," he said. "It is better to look at what Bergoglio has done since becoming a bishop – the concern he has shown for the poor and for street dwellers. This is a Jesuit approach."

Francis's commitment to the poor, the sick and the marginalised is indubitable and profoundly Jesuitic. He is a familiar figure in a giant slum in Buenos Aires, known only as 21-24, where 45,000 people live in extreme poverty. For 15 years, Bergoglio rode the 70 bus several times a year, and then walked in normal priest's robes through the dangerous neighbourhood to celebrate mass at the tiny makeshift church of the Virgin of Caacupé.

"He is adored by everyone here, I would say you'd find a photo of him in 60% of the homes in 21-24," said Father Juan Isasmendi, who holds Bergoglio in an almost saintly regard. For the priest, Bergoglio was a rarity in the Argentinian Catholic hierarchy. "He is a true man of God, he baptised so many children, he gave communion himself to thousands here. He is authentically religious, a true pastor, he was a father to so many people here and a father to us priests."

As archbishop of Buenos Aires, he famously gave up the palace in favour of a modest flat where he cooked for himself, and chose to move around the capital on public transport rather than in a chauffeur-driven car. And, just as he did when he became a cardinal in 2001, he has asked people not to travel to Rome for his installation mass, but to give the money they would have spent to the poor.

Such behaviour has endeared him to millions. Yet Estela de la Cuadra – whose mother co-founded the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo activist group during the dictatorship to search for missing family members – seems resolutely immune. Asked whether she felt Francis had lived up to his reputation as a common, humble man, she replied, ironically: "Yes, he has an arrogant humility."

But Francesca Ambrogetti, co-author of a flattering biography of the new pope entitled The Jesuit, feels that Francis's compassionate and practical attitude to the disadvantaged will be one of the distinguishing features of his papacy. "He is very close to people, though that is not often realised," she said. "In the future, he is looking towards a more missionary church, a church that goes out to meet the people."

She points to the parable of the shepherd who leaves 99 sheep in his flock to look for the one animal that is lost.

"For him, it is the opposite," said Ambrogetti. "There is one sheep in the fold and 99 lost. I think this convinced the other cardinals – the emphasis on a missionary church."

And what of the name of the book? Does Francis still see himself as a Jesuit?

"He wasn't against the title of the book," she said. "When we asked him to define himself, his answer was: 'Jorge Bergoglio, a priest'. But he accepted the title."

Despite his missionary vigour, however – and a readiness to engage with the secular world that far outstrips that of his predecessor – Francis remains an outspoken opponent of abortion, divorce, women's rights and euthanasia.

"A pregnant woman is not carrying a toothbrush in her womb, or a tumour," he once said. "Science shows us that the entire genetic code is present from the moment of conception. It's not therefore a religious issue, but scientifically based morality, because we are in the presence of a human being." He has also said that women who terminate their pregnancies suffer "giant dramas" of conscience, and defended the withholding of communion from divorcees.

Tina Beattie, professor of Catholic studies at Roehampton University, is not surprised by his past pronouncements.

"He's conservative on sexual issues but they all are," she said. But, she added, Francis's personal experiences of, and commitment to, the marginalised might yet lead him to confront some of the issues that Benedict XVI was simply unable to grasp.

"If he is listening to the voices of the poor, he will hear things about women's lives that the last pope was totally deaf to and unaware of," she said. "Any pope who listens to the poor and struggling people will hear women's voices if he really wants to."

The new pope's plans for the scandal-wracked Curia, the Vatican's civil service, are harder to fathom. Will he bring a Jesuit's rigour and force to the problem and drive the thorough reform of which the Curia is so badly in need?

"Every office in the Roman Curia is up for grabs," said Walsh. "But where's he going to get the people who are going to reform the Curia with him? He doesn't know how the Curia works very much because he's not been a curial man – which is a good thing in one way – but you do need to know how it works in order to reform it."

Although at least one previous declaration suggest Francis may not view reform of the Curia as the most pressing issue – "sometimes negative news does come out, but it is often exaggerated and manipulated to spread scandal" – Walsh believes a Jesuit pope may bring two new attributes to the office.

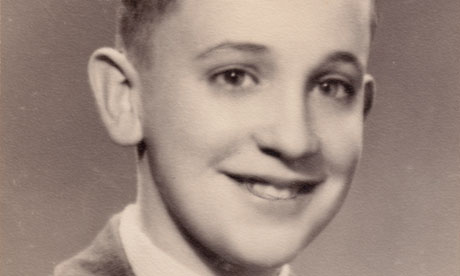

Pope Francis as a teenager in Buenos Aires. Photograph: AP

Pope Francis as a teenager in Buenos Aires. Photograph: AP

"Jesuits consult a lot," he said. "I really think we'll see a pope who's going to consult more; I think we're even seeing signs of that now in his way of dealing with the cardinals and not putting himself above them."

What's more, he added, Jesuits tend to leave the offices they hold – whether as provincials or school principals – after a six-year term, raising the prospect of a short papacy.

"Since they appointed someone of 76, they might very well have thought that he was going to follow Benedict's example and retire," he said.

Regardless of the precedent, talk of retirement is, of course, premature – not least for Pope Francis's only surviving sister, María Elena Bergoglio, who is still trying to come to terms with the fact that he is now the spiritual leader of 1.2 billion people.

Almost 60 years have passed since the spring day when the 17-year-old Jorge Bergolio first felt the tug of vocation, a stirring that led him to leave his friends to their día de la primavera celebrations and head instead to confession at the church of San José de Flores. His decision to devote his life to God delighted his father but angered his mother; his election as pope has stunned but delighted his surviving sister.

"He looked very happy, very relaxed and happy," said María Elena of the moment he stepped on to the balcony of St Peter's to greet the world.

Despite her pride in his achievements, though, María Elena won't be going to Rome to see him installed.

"I'm staying here in Argentina," she said. "This where I feel I have to be, praying for this very difficult world we live in, praying for this very difficult moment for the church."